This law is the basis for Germany’s Energiewende and specifies 1. priority dispatch for renewable power and 2. floor price for that electricity. The resulting high level of investment security and the lack of red tape are the main reasons why the EEG has brought down the cost of renewables.

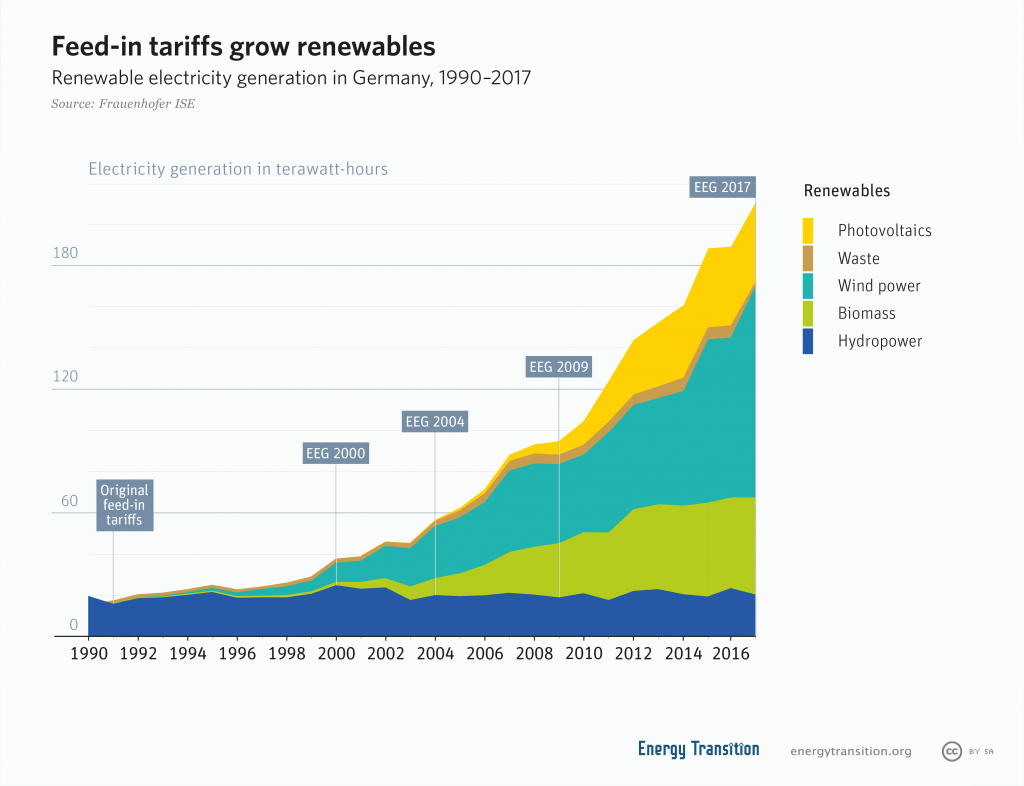

Perhaps no other legislation has been copied worldwide as much as Germany’s Renewable Energy Act (EEG), making it a tremendous success story. Established in the 1990s, it promoted electricity from renewable energy sources, including wind power, solar energy, and small hydropower generators.

The EEG sets very ambitious targets. For instance, Germany plans to get at least 40 to 45 percent of its power from renewables by 2025, and at least 80 percent of its power from renewables by 2050. This legal requirement to switch power generation almost entirely to renewable sources is one of the main pillars of Germany’s Energiewende.

Priority dispatch

Renewables have “priority dispatch” on the German electrical grid, meaning that the grid must take up power from wind, solar, and biomass even if sources with no priority (such as coal, gas, and nuclear) have to be curtailed.

Grid operators are required by law to purchase renewable power, with the result that conventional power plants have to ramp down accordingly. In the process, renewable power directly offsets conventional power production.

Under the EEG, owners of solar arrays and wind farms have guaranteed access to the electrical grid. The EEG specifies that green electricity is sold to the grid operator, which cannot refuse the contract. Without the EEG, renewable energy projects in Germany would have had to find a buyer for that electricity. Most utilities would have rejected the offer outright, arguing that these third party investments conflict with their existing assets.

The EEG thus opened up the power market to newcomers, who believed they could make solar and wind work. If the transition had been left to utilities with conventional assets to defend, it would never have progressed as much.

Feed-in tariffs

Feed-in tariffs are made up of the cost of a given power system per kilowatt hour (for example solar or wind), plus a pre-determined return on investment. This is the part that guarantees some small profit to owners. In Germany, the target return on investment, or ROI, is around five to seven percent.

In 2000, these feed-in tariffs were revised, expanded, and increased; every three to four years, they were subsequently reviewed and the law was amended. The last major revision of the law was undertaken in 2016 to coordinate a switch from feed-in tariffs to auctions as the main policy for larger renewable energy projects. Feed-in tariffs remain in place for solar and wind below 750 kW.

In Germany, the standard contract for feed-in tariffs that you sign with your utility is two pages long for solar. In contrast, the United States has Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), which can easily be 70 pages long and are individually negotiated between the seller and the buyer. In Germany, feed-in tariffs are guaranteed for 20 years, which would be unusually long for PPAs. And let us not overlook one important aspect – you will need a lawyer, if not a team of lawyers, to formulate a PPA, whereas the average German has no problem understanding the two-page contract for feed-in tariffs.

EEG 2016 and the switch to auctions

In 2017, Germany phased out feed-in tariffs for large systems and switched to auctions, in which the buyer receives bids from sellers. This was fundamental shift change from the system that was based solely on feed-in tariffs. Pilot auctions already began in 2015 for ground-mounted solar.

The average final price for solar PV in early 2018 was 43 euros per megawatt hour – quite an accomplishment for a relatively cloudy country. There were some concerns as well, based on outcomes of auctions in other countries, that projects may not be completed on time. However, 96 percent of the projects from the first pilot auction held in April 2015 were finished by the deadline two years later. The German government is therefore happy with the progress.

When praising the price results at auctions, it is important to keep these deadlines in mind. If a project has years to finish, bidders estimate where prices will be in the future. For instance, in 2017, Germany launched its first auctions for offshore wind. The result was that some bidders offered to accept the wholesale rate, leading many onlookers to report that “subsidy-free” offshore wind power had finally arrived. However, those projects have until 2025 to finish. In addition to likely further reductions in equipment prices, wholesale power prices are expected to rise in Germany, largely because the nuclear phase-out will remove nearly 10 GW (some 10 percent of the total installed capacity) by the end of 2022, thereby doing away with the excess in baseload capacity currently causing the unprofitable low wholesale rates.

Critiques of renewable energy auctions

In 2017, Germany also held its first auction for onshore wind, and the outcome was surprising: more than 90 percent of the volume went to bidders that fit the category “community projects”, which were specifically defined by the EEG in 2017 for the first time.

Cooperatives had argued that they would not be able to compete under an auction design because they often only pursue a single project or a small number of projects. In other words, they would not be able to spread lost revenue from losing bids across multiple projects, like larger companies can do. They therefore asked to be included in the category “non-competitive bidder,” meaning that they could build their projects at the strike price from the auction.

The compromise reached allowed community projects to place non-competitive bids without having all their permits granted; the permit process can be expensive, and a losing bid could cost a six-figure sum. However, following complaints that some of the “community projects” were actually developers who had organized groups, the process was revised again.

Now, community projects must be for projects of six or fewer wind turbines, with a maximum 18 megawatt capacity. In addition, the “community” must consist of at least ten people, more than half of whom have lived where the wind farm will be constructed for over a year. In addition, the voting rights must be shared equally between members: nobody can have more than 10 percent of the vote.

In 2018 a new type of auction was tried for the first time: a technology-neutral auction, with onshore wind and solar PV pitted against each other. The goal was that both would compete on an equal footing, but wind was at a clear disadvantage – solar bids won the day, but at higher prices than previous (technology-specific) auctions. Solar and wind associations were displeased with the results, as was the economy minister, who commented that the Energiewende needs a mix of technologies to succeed.

Solar remains close to the annual minimum target of 1.5 megawatts. Now, arrays larger than 750 kW will no longer be eligible for feed-in tariffs and instead have to be auctioned. Below that level, solar will increasingly offset power purchases from the grid, but the governments wants to rein in this potentially strong market as well. If more than 20 MWh of solar power is consumed directly, the electricity tax of 2.05 cents per kWh is payable for the entire amount of electricity in addition to roughly 2 cents for the renewable surcharge. Solar power from new arrays may only cost nine cents, but the German government is adding four cents to systems of this size. Mainly, very large commercial roofs are affected.

New biogas plants will only receive feed-in tariffs for half of the hours in the year. They will then focus more on producing when wholesale power prices are high. In other words, biogas is being made flexible to complement wind and solar.