Most Germans agree that the transition to renewable energy is crucial – but it will require a complete societal change.

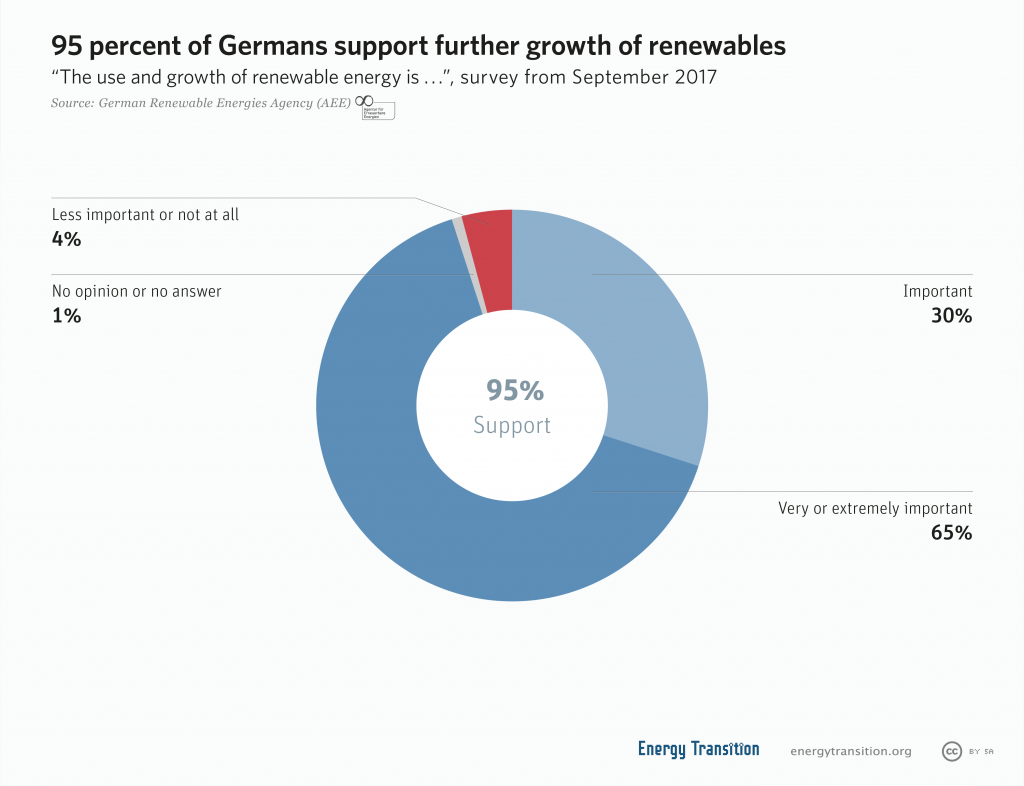

Germans overwhelmingly support the energy transition: 93 percent support the further growth of renewables, and 76 percent believe it will make the future safer for their grandchildren.

A societal change also requires a shift in thinking. This cultural shift of the Energiewende cannot be completed overnight, but will take time and require a lot of awareness-raising.

Germany is a society in which people love their creature comforts, so as all of these devices become more efficient, we must ensure that people do not simply decide, say, that a car with twice as good gas mileage means they can drive twice as much for the same price. People will need to think about cars differently if transportation emissions are to decrease (rather than increase as they have in the past years).

Agora Energiewende suggests that future cities will need far fewer cars: currently, German cities have about 450 cars per thousand inhabitants, but carsharing could lower that number to as little as 150 if they are shared.

Programs like car sharing can transform a car from something which is owned and stored to something which is used as necessary, and clear up city congestion and air as well. It’s possible (and cheap) not to own a car, and use whatever method of transportation fits best. If you want to move a case of beer across the city, grab an electric bike; if you need to go to Ikea, use an electric car for a few hours.

Increasingly, new modes of flexibility will need to be tried out, however. Housing associations are working on flexible housing concepts to allow rooms to be easily separated in order to put an end to the unbroken growth in per capita living area over the past few decades. Elsewhere, residential complexes now have ultra-efficient washing machines for common use in the basement.

This discussion about policies to change behavior is just getting started in Germany. Already, it is clear that new ownership and financing models (such as energy cooperatives) will not only allow people to get involved in new ways, but also increase acceptance of local change and awareness of energy consumption.

Geographical inequalities

There are some ways that the Energiewende is more beneficial to people who live in the city. For example, they are much more likely to have access to well-developed networks of public transportation so it is easier not to own a car. In terms of climate initiatives, it also often makes sense to target city transportation improvements because this delivers the best per-capita reduction in emissions. For example, politicians have proposed that public transit should be free in some German cities – obviously, this benefits those residents.

Some ways that both cities and rural areas benefit from the energy transition is by municipalizing their utilities, and demanding that they use sources of clean energy. Municipalizing means that rather than having a company provide a service and then pocket the profits, the city can benefit directly. This is especially true for energy grids. In Germany, the city of Hamburg voted for the city to buy back its energy grid from Vattenfall, due to a demand for “a socially equitable, climate-friendly and democratically controlled energy supply from renewable energy.”

There are some regional disparities in Germany of who has received the most benefits of the energy transition. This often falls along the East/West divide – Bavaria’s sunny south has a solar panel on every roof, but Brandenburg (the old East) still has reserves of brown coal. In general, the post-socialist German states are less likely to take advantage of subsidies (especially those for biogas) – there is therefore still a need for more information and support in those regions.