Germany began building highly efficient passive houses in 1990. But although many buildings can now be renovated to fulfill very ambitious standards, a lot of progress still needs to be made towards increasing the energy efficiency of renovated buildings. To improve things, Germany has developed an Efficient Building Strategy.

In Germany, roughly 35 percent of all energy is consumed in buildings, most of it for heating. This area is crucial in Germany’s energy transition because most renewables produce electricity, which makes up the smallest part of German energy consumption at 20 percent. In contrast, oil and gas continue to dominate the heating sector with a combined share of more than three fourths of the heat market.

Building retrofits – the area that requires the most attention

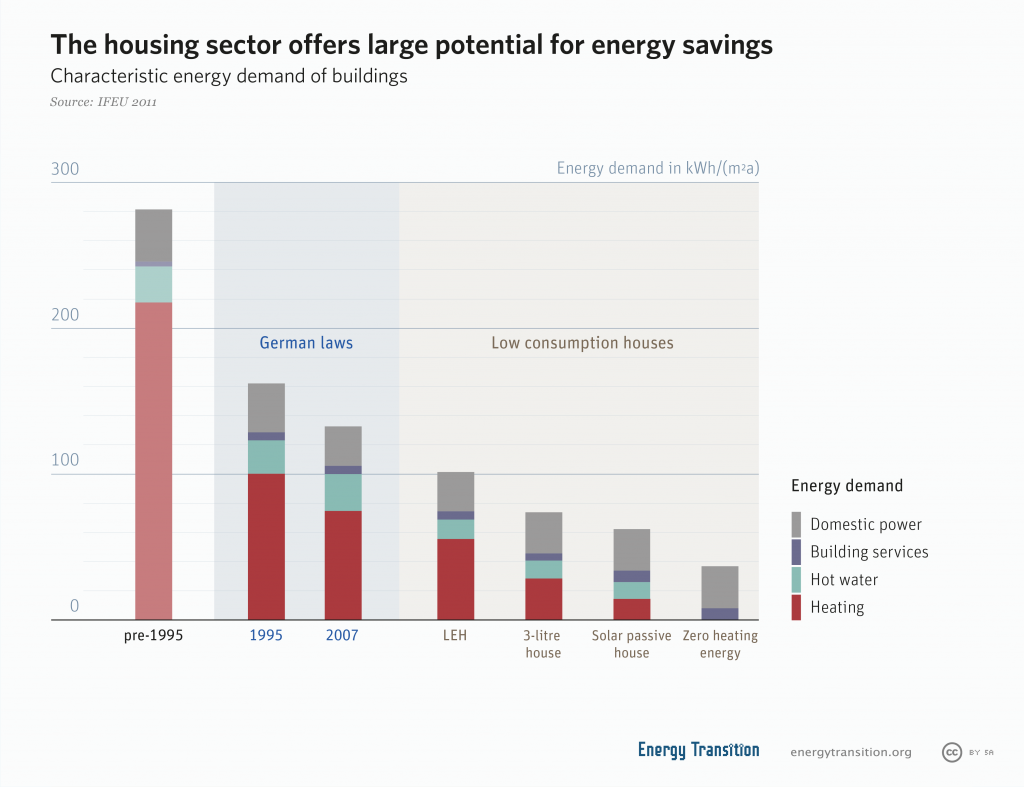

In Germany, most of the energy used for heating, cooling, and hot water is consumed in buildings, most of which were built before 1978, when Germany implemented its first requirements for insulation. For instance, two-thirds of the roughly 15 million single-family homes and duplexes were constructed at a time when there were no requirements for insulation. These buildings use up to five times as much energy as those constructed after 2001. The energy transition has yet to take proper account of the potential from renovations. Instead of ensuring that renovations are as comprehensive as possible, German law has generally encouraged building owners merely to make the most urgent minor repairs.

In other words, the low renovation rate is not the only problem; not enough is done during renovations. Buildings are not properly insulated during renovation, and the technologies that would pay for themselves the most are not used often enough. As a result, buildings renovated today will soon need to be renovated again.

The reasons for these shortcomings include a lack of awareness, a lack of motivation, financing problems, low returns on investment in the short run, and insufficient skills among firms, planners, and tradespeople who perform renovations. The government has attempted to address this issue through campaigns to raise awareness for both private residences and businesses (which use a disproportionately large amount of energy compared to homes). But renovation rates remain low: only about one percent of the German housing stock is renovated per year.

The dilemma of tenants and landlords is another major issue. Building owners do not have proper incentives to invest in renovations that merely lower the utility costs for their tenants. The situation is especially serious in Germany, where 24 million of the country’s 41 million households do not own their own homes.

Trying to improve the situation

At present, Germany is focusing on increasing its renovation rate from one percent per year (meaning that all buildings would be renewed within 100 years) to 2 percent (so that all buildings would be renewed within the next 40 years). Since 2000, about five million renovations have been carried out. The potential for savings is enormous: a recent study found that it is technically possible to decrease primary demand in buildings by 80 percent, but the current policy is not enough to achieve this goal.

The Energiewende has made great progress when it comes to electricity, for which a number of policy tools have been implemented, but progress in building renovations has been slower. If things are to speed up here, policies will have to be changed. The Energy Conservation Ordinance (EnEV) includes requirements for energy audits, replacements for old heating systems, and the quality of renovation steps. However, that last point is only effective if renovations are actually carried out. In Germany, there is no legal tool for speeding up retrofits.

Instead, Germany is focusing on information and financial support. Germany’s development bank KfW provides special low-interest loans for energy-efficient renovations, although more than 50 percent of this funding is still devoted to new buildings. Furthermore, laws protecting the rights of tenants were revised in 2012 to help encourage building owners who rent their properties to invest in renovations.

What is needed is a substantial increase in funding for retrofits. Low-income families often live in poorly insulated buildings and therefore face high energy costs, and are at risk of energy poverty. Yet, building owners are not willing to invest in renovations because they will not be the ones who benefit from lower utility bills. The only way around this dilemma is providing funding for renovations in such situations, but the energy transition has yet to address this problem sufficiently.

As part of the National Action Plan for Energy Efficiency (NAPE) of 2014, new programs have been developed which address non-residential buildings – an area neglected so far. New tools for energy consultancy are being developed. For instance, the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research develops a tool called “individual renovation roadmap” which specifically helps owners with ambitious step-by-step renovations. Unfortunately, one of the major instruments proposed in the NAPE, a tax break for renovations, did not pass the Bundesrat (Upper House) because of objections of a few Federal States.

In 2015, a new policy (“Hauswende”) intended to get weatherization efforts going again. The German Environmental Ministry has created this special project called “Hauswende” to facilitate the focus on energy conservation in renovation projects, which are often complex and include several trades. Additional efforts within the NAPE include a new labeling scheme for existing heating systems as well as a “heat check”, a program carried out by chimney sweepers and installers, meant to increase the dynamics of heating modernization. In 2016, the maximum allowed demand under the EnEV for primary energy needed to be 25 percent lower than a “reference building.”

It would also help to move beyond building renovations and look at how entire neighborhoods and city districts can be made more energy-efficient. In 2012, the development bank KfW started a special and successful support scheme entitled “Energetische Stadtquartiere” (“Energy in urban neighborhoods”) that provides financial incentives to municipalities to plan, organize, and implement district-wide retrofit schemes and to implement district heating networks. In addition, within the urban development promotion programs and another programs targeted towards municipalities, efficiency measures and the installation of renewable and district heating infrastructure is funded.

The Energy Conservation Ordinance (EnEV)

In 2002, Germany adopted its Energy Conservation Ordinance (EnEV). For the first time, this legislation provided a way of creating an eco-balance for a building by counting not only the useful energy provided to the building, but also the primary energy needed in the process, which includes losses in generation, distribution, storage, etc. In addition, EnEV includes requirements for the quality of renovation steps, energy audits, and replacements for old heating systems. The current EnEV specifies that new homes must not consume more than 60 to 70 kilowatt-hours of energy per square meter of heated indoor area per year for heating and hot water.

The EnEV was amended in 2016 because the government had to introduce the nearly-zero energy standard as required by the European Buildings Directive. New public buildings must be built along zero-energy guidelines by 2019, and all other buildings must be zero-energy by 2021.

Passive Houses

Way back in 1990, a number of German architects built houses that make do with only 15 kilowatt hours of heating energy per square meter – the first passive houses. So little energy is needed for heating that some residents of passive houses simply invite friends over for dinner when the apartment starts to get cold. Heat from the kitchen and from human bodies suffices to warm the house.

Passive houses basically allow you to completely do away with heating systems even in a cold climate like Germany’s. Heating expenses are cut by an estimated 90 percent compared to a conventional new building, partly because backup heating systems can be so much smaller.

Passive houses are a combination of high-tech and low-tech. The low-tech aspect is relatively straightforward: homes are built facing the south in Germany. The southern façades have large glazed surfaces to allow a lot of sunlight and solar heat in during the cold season. In the summer, overhanging balconies on the south side provide shading, thereby preventing overheating, as do deciduous trees planted on the south side of the building, which provide additional shade in the summer but lose their leaves in the winter to let the sunlight pass through.

The high-tech aspects mainly concern the triple-glazed windows, which allow light and heat to enter but largely prevent heat from exiting the building. Most importantly, passive houses have ventilation systems with heat recovery, which also help prevent mold.

In short, passive houses are an excellent example of how Germany’s Energiewende will produce much higher standards of living even as energy consumption is reduced and made more sustainable.

Plus-energy homes

Some cities in Germany (such as Frankfurt) already require the Passive House Standard for all new buildings constructed on property purchased from the city. The EU has also stipulated that all new buildings will have to be “nearly zero energy” homes starting in 2020.

And when solar roofs or other ways of direct renewable energy supply are added to passive houses, you end up with homes that essentially produce more energy than they consume – at least in theory. Called plus-energy homes, or, in the terminology of the KfW, Effizienzhaus Plus, such buildings are not, however, off the grid; rather, they export solar energy to the power grid at times of excess production and consume power from the grid at other times. And of course, any gas needed for cooking purposes, etc. also has to be purchased as usual.