Sun-drenched and zephyr-kissed, Spain occupies a corner of Europe that is ideal for solar and wind power. After an initial surge of investment in renewables, the flaws of the government’s energy policy became evident, and the authorities slammed the brakes on investment. There are signs that they may now be relenting.

Renewable energy in Spain

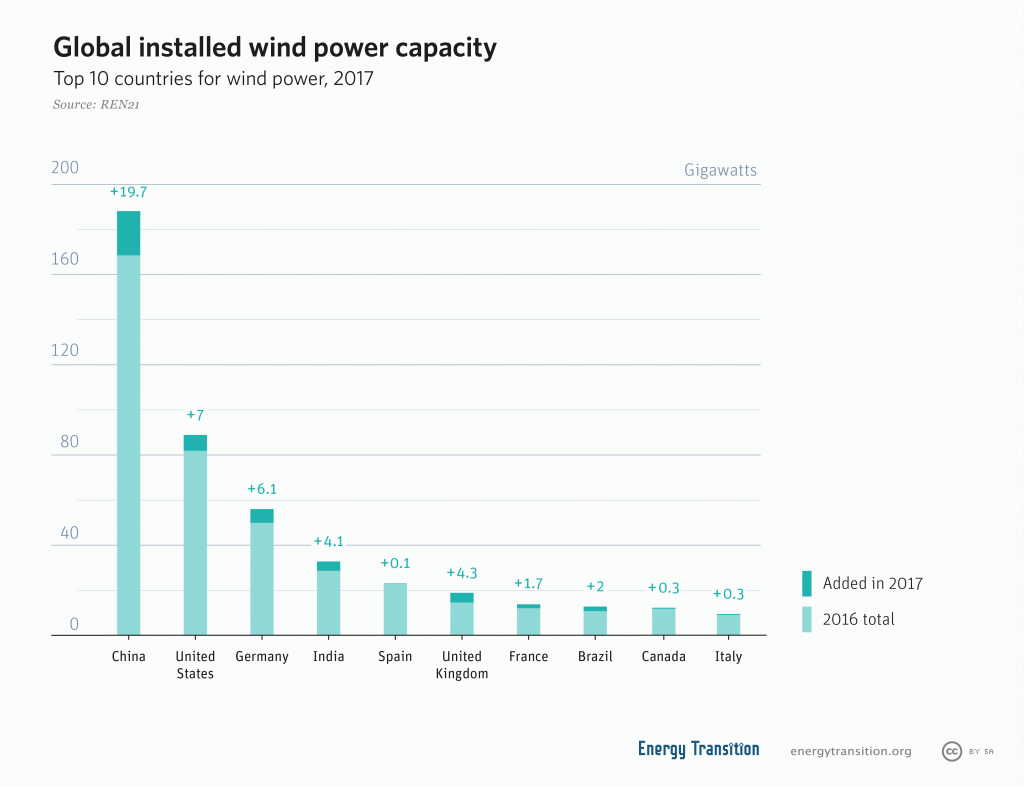

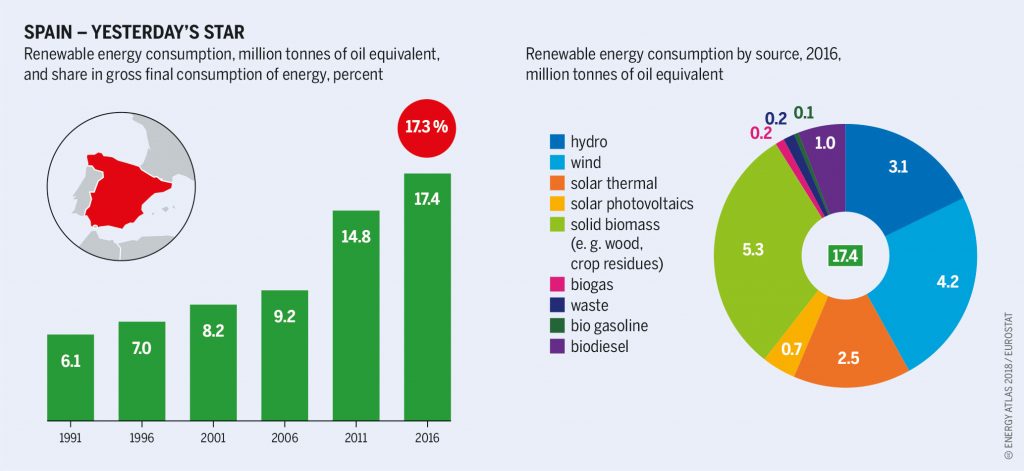

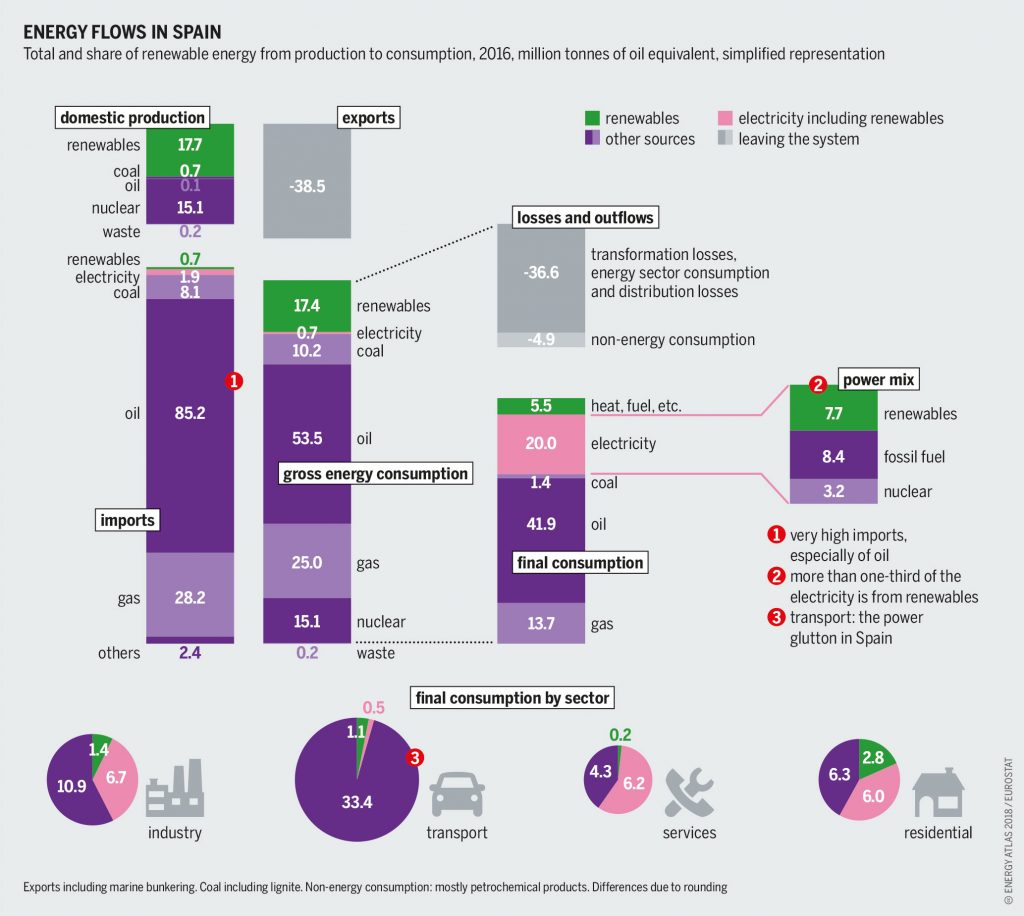

With its windy mountains and plains, and many hours of bright sunshine each year, Spain has huge potential to develop renewable energy. In 2016, wind was the dominant source of power from renewables, which as a whole already contributed close to 40 percent of the electricity

generated. In Europe, Spain is second only to Germany in terms of wind-power generation; it is fourth worldwide.

Wind power contributes around 18 percent to gross electricity consumption, followed by hydropower with 13 percent. Solar photovoltaics have huge potential but so far provided only 3 percent to the country’s electricity mix. According to Greenpeace, Spain’s renewable sources could generate much more electricity than the country currently uses.

Spain slows renewable targets

The government’s goal is to reach 20 percent renewables in total energy consumption (including heating and transport) by 2020. Between 2004 and 2012, the share of renewables in the overall energy mix grew from 8.3 to 14.3 percent, and Spain was regarded as an international leader in the field.

However, policy changes have stalled this growth. An interim target was 16.7 percent for 2015, but Spain fell short by 1 percent. Experts now find it hard to believe that it will achieve the remaining 4 percent by 2020. They fear that Spain is jeopardizing its leading role.

The previous strong growth was driven by an effective feed-in tariff policy for renewables. This set a generous payment, especially for solar photovoltaics, and no overall ceiling for new installations. But the surge in investments led to significant overcapacity as new installations came on line, while demand stalled because of the economic crisis. Meanwhile, older conventional plants were not retired to make way for the renewables.

A poorly designed electricity-tariff system is at the root of the problem. The government compensates energy firms if the generation costs are higher than the amount the firms are allowed to charge their customers. Bills for such compensation have ballooned, and the state now owes the firms a huge sum: €25 billion, or 2.5 percent of the gross domestic

product.

Between 2012 and 2015, the government made several changes to the policy, reducing future support and even introducing retroactive cuts. It is trying to tackle the deficit in three ways.

- First, it has increased the price consumers are charged for power – especially those who use less than 20 megawatt hours (MWh) a year, which includes households and small businesses. As a result, electricity prices have risen to nearly €300 per MWh, one of the highest in the EU.

- Second, it has weakened the feed-in tariff policy by cutting payments for renewables. That, in turn, has created further uncertainty in the renewable sector. The costs of the so-called tariff deficit have fallen at the expense of renewable energy deployment. More than 80,000 workers in

the renewables sector have lost their jobs. - Finally, the government has limited its promotion of renewable energy. It introduced a “sun tax” on self-consumption facilities (such as solar rooftops), arguing the tax was needed to cover additional system costs. Owners of solar panels must now pay a fee to maintain access to the network if they consume the electricity they themselves produce. This measure forces the owners to feed their excess power into the grid at low prices, depriving them the benefit of their own power. Levels of self-consumption have fallen to near zero as a result.

These changes have caused a lot of uncertainty, and investment in renewables has dropped. In 2012–15, their share of final energy consumption rose slowly, from 14.3 to 16.2 percent, making it one of the slowest rates in Europe.

Between 2013 and 2015, installed wind power grew by more than 20 percent in Europe as a whole; in Spain, it rose by only 0.07 percent. The situation for photovoltaics was no better:

generation grew by 15 percent in Europe as a whole over the same period, but in Spain by just 0.3 percent.

On the bright side, the public energy debate has gone from being non-existent to a hot topic, blending themes such as the need for a more sustainable society and for democratic energy management. Today, cooperatives and marketing companies are multiplying, and municipal initiatives are focused on developing sustainable energy, self-generation and democratization of the model. It seems likely that citizens will push national energy policy in a sustainable direction.

Spain offers ideal geographical conditions for the development of renewable energies. Its potential for large-scale wind and solar power is among the highest in Europe. But renewables face a hostile regulatory and political environment, with the government trying to control costs and protect old power plants by preventing a further boom in renewables. However, such domestic constraints may be weakened soon.

A revised EU Renewable Energy Directive could push Spain to take a more proactive stance on its energy transition. Renewables may then regain the legal and investment security needed to bring about Spain’s energy transition.