Germany began switching to renewables in the early 1990s. Nowadays, onshore wind power is the cheapest source of new renewable power and made up around 20 percent of the country’s power production in 2018.

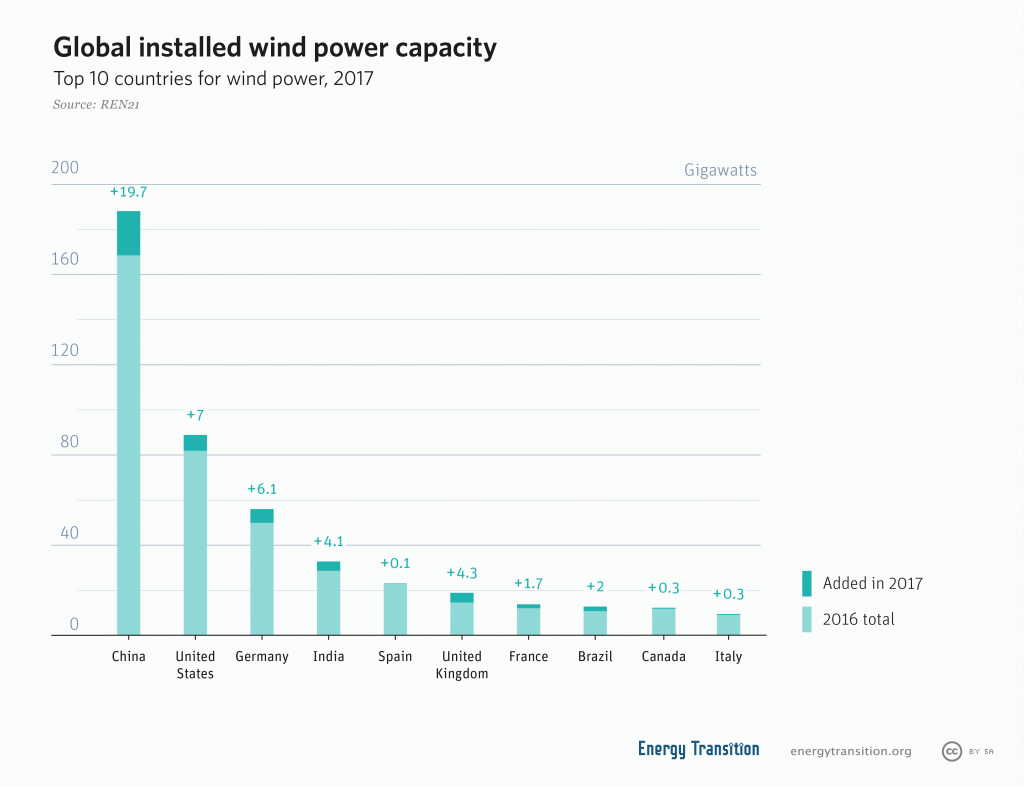

Wind power in Germany began as a small, community-owned movement and has grown to push out coal power. In 2018 Germany got roughly 20 percent of its electricity from wind turbines, most of which were onshore. While the country used to be a world leader, it has now been surpassed by China and the US for installed wind power.

Onshore wind turbines are mainly owned by midsize firms, cooperatives and small investors. Offshore wind, owned by energy utilities, has made a promising start, accounting for 2.8 percent of power production.

Onshore wind power in Germany

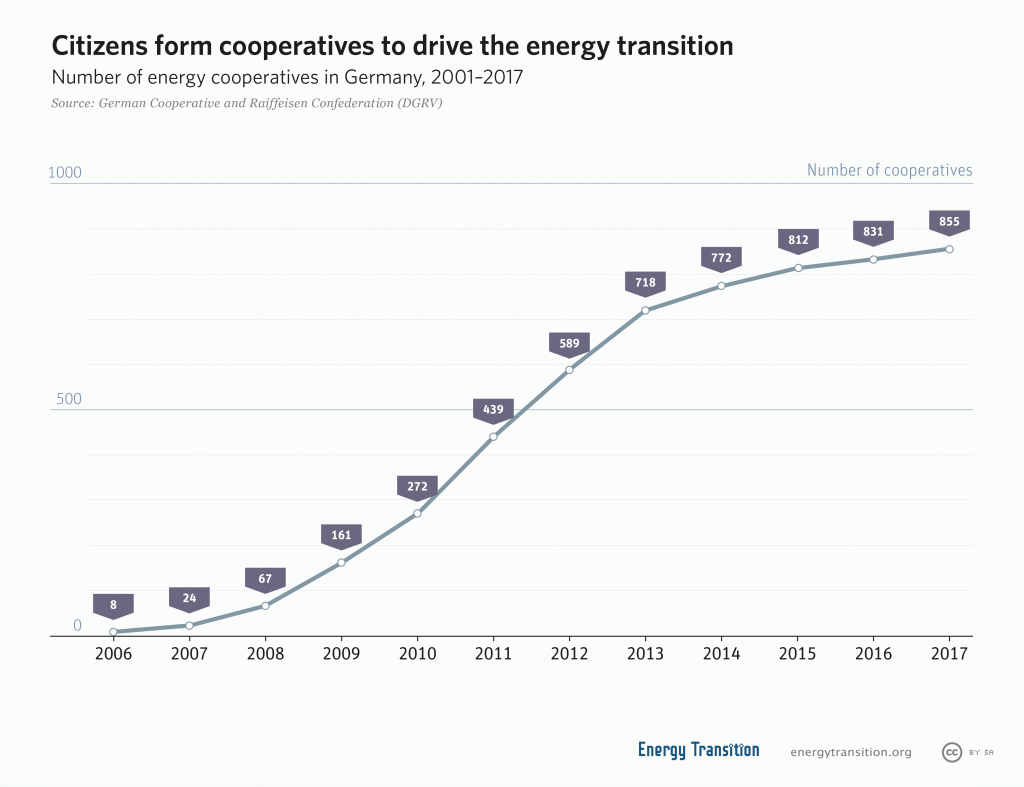

The German wind sector has traditionally consisted of community-owned projects that grow “organically”: a few turbines are put up, and when the community realizes what good returns the wind farm provides its investors, more people want to get involved and install new turbines.

As the turbines go up, people also realize that concerns about noise are exaggerated. Internationally, concern about the health impact of wind turbines is restricted to places with very few of them. Health effects are less an issue in the debates in Germany and Denmark, the two countries with the greatest density of wind turbines.

On the contrary, people realize that the health effects are positive when clean wind power replaces dirty coal power and potentially dangerous nuclear power. Finally, as the wind farms grow, people get used to the “visual impact” and start to see the turbines as no more intrusive than power pylons, buildings, and roads – and less noisy than cars.

Thanks to the technical developments seen in recent years, the use of wind power has also become more attractive in inland regions. In southern Germany – especially in the southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg, which still has very little wind power – planning barriers were removed to facilitate the installation of wind turbines on hillsides and in forests. At the same time, new turbines must fulfill strict ecological criteria. The state of Baden-Württemberg is one of Germany’s most economically strong states, but has nevertheless decreased its energy use by around 11% in 2017 compared to 2008, and gets 21% of its energy from renewable sources. Of these, wind power makes up 3.5% of the final energy mix (with a goal of reaching 10% wind energy in the power sector by 2020).

Policies for onshore wind: Feed-in tariffs vs auctions

For many years, the German government encouraged investments in renewable energy with feed-in tariffs. After the huge increases in renewable energy, the law which decides how renewables are subsidized was changed. Now, permits for energy projects are determined by auctions, and only very small renewable projects are eligible for feed-in tariffs.

Just before the switch from feed-in tariffs to auctions in 2017, large amounts of onshore wind power were added: in 2016, 4.3 gigawatts were added, and in 2017, a record high of 5.3 gigawatts. In addition, a number of federal states improved the conditions for onshore wind, removing some of the barriers for wind installations.

In the first round of onshore wind auctions held in 2017, special conditions were set for bids that fit the definition of “citizen projects”. Specifically, the environmental impact assessment did not yet have to be available at the time of bidding, and these “citizen projects” were eligible for the highest winning bid price regardless of the price at which they actually bid. As a result, more than 96 percent of the first auction round went to these specific projects.

Even Green Party representatives feel that this share is too high, so future auctions are likely to be redesigned as to allow for commercial bidders to have a share of the cake as well. There have also been reports that numerous commercial players have already gamed the system so as to compete as a “citizen project” by getting their own employees to act as independent citizen investors.

Repowering old wind turbines

The offshore sector differs greatly from traditional onshore wind; while the latter mostly consists of midsize firms and distributed wind projects owned largely by communities and small investors, the former is almost entirely in the hands of large corporations and utilities, many of which initially opposed the switch to renewables.

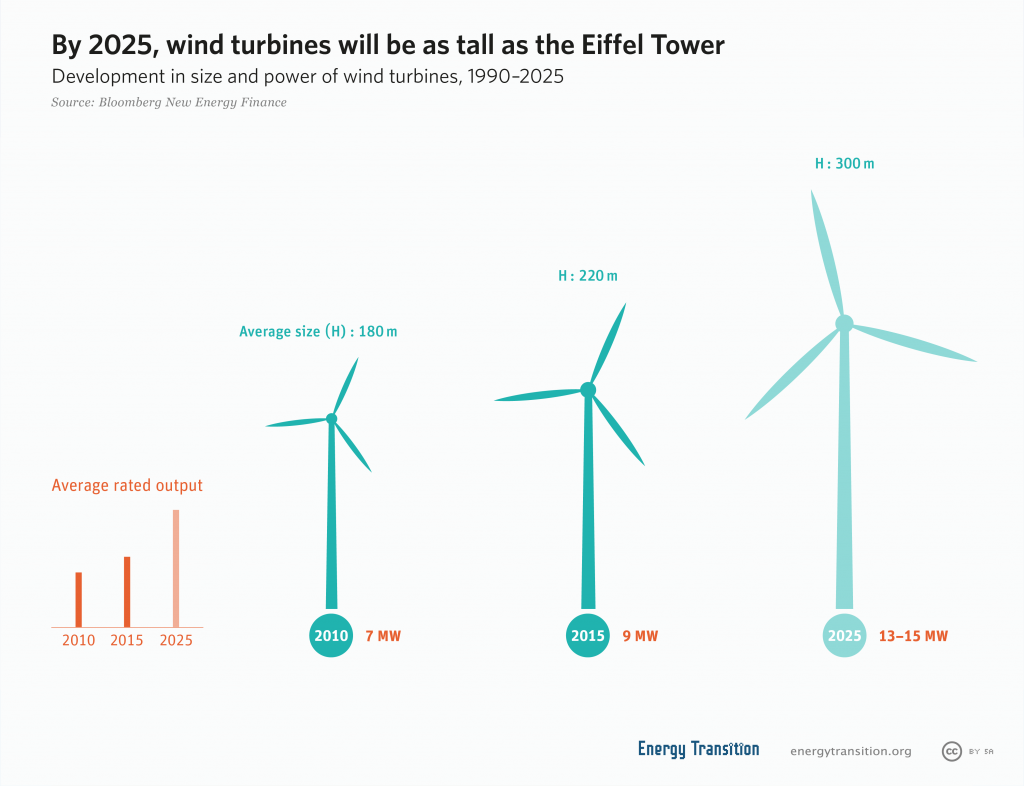

The traditional onshore sector therefore argues that older onshore wind farms should be repowered; turbine technology has made great advances since the 1990s, so far fewer turbines can now produce much more power. Nevertheless, offshore wind power has made a strong start: offshore wind power production has grown exponentially over the past three years, from only 1.4 TWh in 2014 to almost 18 TWh in 2017.

Repowering is an important issue in Germany. Because the wind sector has been at work here for two decades, the first wind farms that received feed-in tariffs have reached the end of their service lives, and even the ones that still have a few years left do not use the available space as efficiently as the latest turbines can. After all, the output of an average turbine installed today is about ten times greater than that of the average turbine made in the mid-1990s.

In other words, by replacing old turbines with new ones – by repowering – we can produce ever greater amounts of wind power even as we reduce the visual impact of wind farms. For instance, turbines in 2016 had a rated capacity roughly twice as large as those installed in 2000, and several times greater than those installed in the mid-1990’s. This trend will continue in the future: projections for 2025 estimate that turbines will be about 300 meters tall and have a capacity of 13-25 megawatts.

Offshore wind power in Germany

Germany also has plans for offshore wind power: the government aims to have 6.5 gigawatts installed in German waters by 2020, and 15 GW by 2030. For reference, by 2025, massive new wind turbines could generate as much as 15MW.

The first offshore wind farm, the Alpha Ventus test field, was connected to the grid in 2010, followed by Bard 1 and Baltic 2, the first commercial wind farms, in 2011. Since then there have been steady yearly increases in capacity. 2017 saw continuing increases in offshore wind in Germany, with some 1.2 GW newly installed, bringing the total up to 5.3 GW.

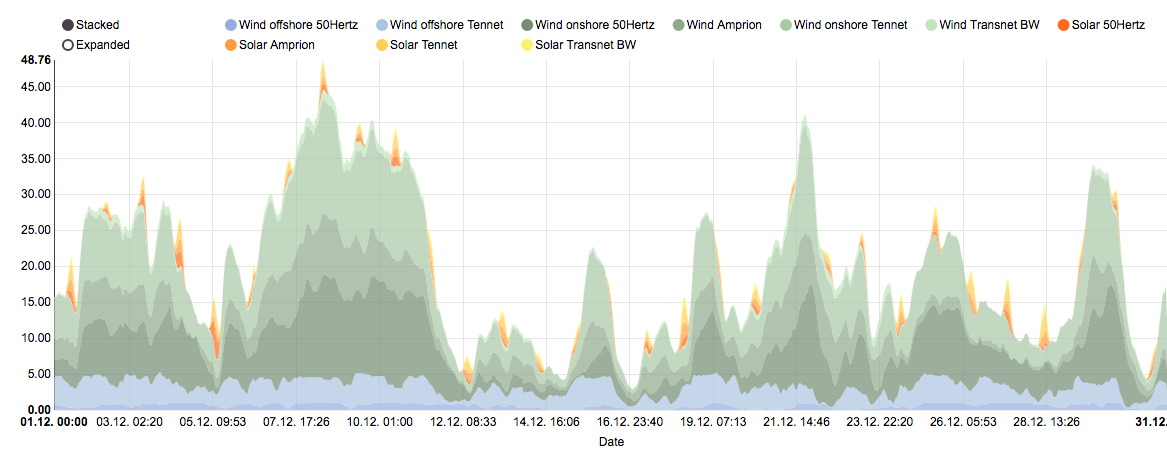

Offshore wind farms are expected to provide power more reliably, as the wind on the open sea is more constant. Recent auctions have shown that offshore wind does not need government subsidies to be built. By 2017, offshore wind already made up 2.7% of the country’s power production, pulling equal to hydro power (which provided about 3.1% of German energy that year).

Offshore wind makes up a solid baseload: pictured in blue, below

Electricity production from wind and solar in December, 2018 (Source: Energy Charts)

Nonetheless, the German wind sector is somewhat lukewarm about offshore wind power because these projects are firmly in the hands of large corporations, whereas onshore wind in Germany is largely owned by citizens; indeed, the Merkel government’s support for offshore wind is sometimes interpreted as a special incentive for Germany’s largest power companies, whose nuclear plants the government is shutting down.