The German nuclear phaseout (in German: Atomausstieg) is the discontinuation of using nuclear power for energy; Germany will shut down its last nuclear power plant in 2022.

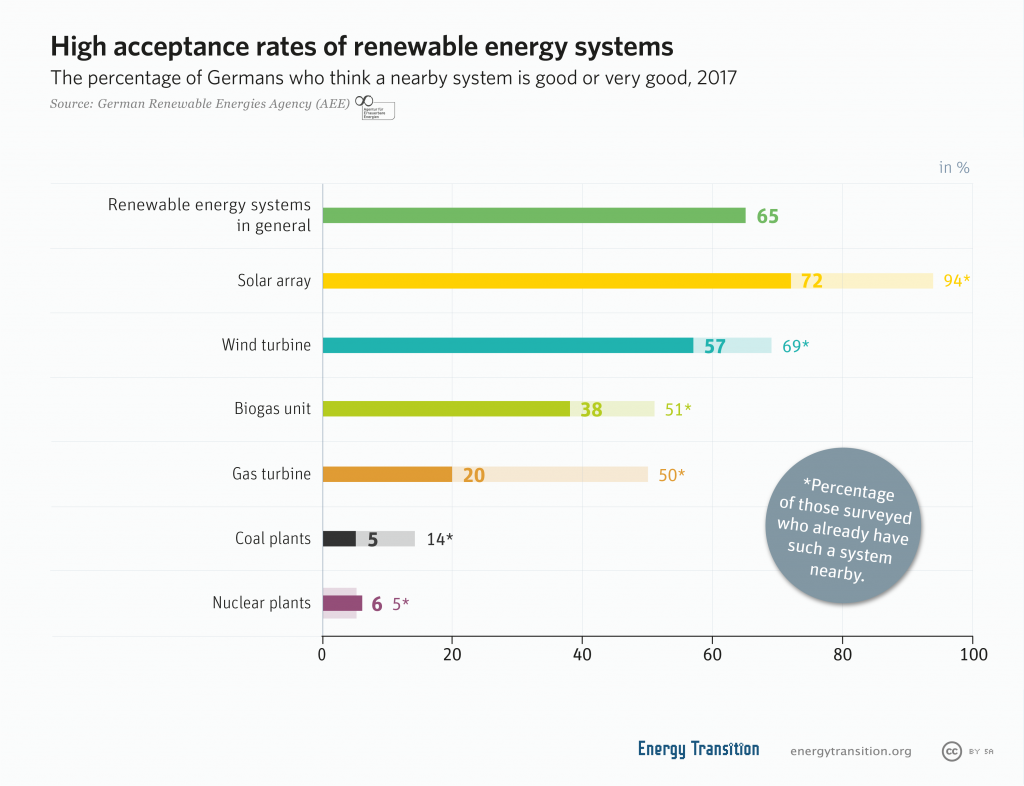

The nuclear phase-out is a central part of Germany’s transition to renewable energy. Germans view nuclear as unnecessarily risky, too expensive, and incompatible with renewables. Only around five percent of Germans think having a nuclear power plant is good or very good.

In 2022, the last nuclear plant in Germany is to be shut down; at the beginning of 2011, 17 were in operation; in 2018, seven were still online. The country plans to fill the gap left behind by nuclear power with electricity from renewables, lower power consumption (efficiency and conservation), and demand management.

Phaseout scheduled in 2000

The 2011 nuclear phase-out was not the first German nuclear phase-out. In 2000, the governing coalition of the Social Democrats and the Green Party under Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder reached an agreement with Germany’s nuclear sector to shut down the country’s nuclear plants after an average service life of 32 years. At the time, the country had 19 nuclear plants with commissions that had not expired.

The firms were allowed, however, to allocate kilowatt-hours from one plant to another. In this way, the firms themselves could decide to shut down one plant ahead of schedule but transfer that plant’s remaining kilowatt-hours to another plant that, say, was located in a more critical area on the grid. Depending on how much nuclear power had been produced by then, Germany would have switched off its last nuclear plant in 2022.

Germany’s Big Four power companies (EnBW, RWE, Eon, and Vattenfall) had no choice but to accept this compromise they had reached with Chancellor Schroeder’s government, but they seemed to have pursued a strategy of waiting it out – and of switching from nuclear to coal and natural gas rather than to renewables.

By the end of 2011, these firms collectively only made up seven percent of Germany’s new investments in renewables. During that same period, the share of nuclear in German power supply fell from 30 percent in 1999 to 23 percent in 2010.

Policy reversals

When Chancellor Merkel took office in 2010, the phaseout law was scaled back: rather than closing all plants by 2022, they were given another twelve years, with the last one closing in 2036. But then came the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima, Japan, on March 11, 2011. In Berlin alone, an estimated 90,000 people took to the streets to protest nuclear power. The German government resolved to shut down eight of the country’s 17 reactors immediately.

The decision became final two months later, essentially meaning that Chancellor Merkel’s coalition suspended the previous nuclear phase-out for only a few months before re-instituting a similar deadline. Now, Germany is back on course to be nuclear-free by 2022. For each of the remaining eight nuclear plants, a concrete date has been set for decommissioning. As of mid-2018, Germany must still close seven of the 17 reactors still online in 2010 before the Fukushima nuclear accident.

Paying for indecision

However, this short suspension of the scheduled phaseout might be very expensive for Germany. Energy companies are now taking legal action for the closure of their plants, claiming that the shutdown cost them 19 billion euros. Utilities E.On, RWE, and Vattenfall have sued the German government, arguing that changing the shutdown dates infringed on their right to property.

In 2016, Germany’s highest court ruled that utility companies could indeed seek damages from German government for the early closures. Vattenfall took Germany to court with the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ISCID) and is suing for 4.7 billion euros. Although Germany tried to argue that the case is in the European Court of Justice’s jurisdiction and outside of ISCID’s, as of September 2018 the court has decided to continue.

In addition to these expenses, the German government must also find a way to finance the decommissioning of the remaining plants and the final waste repository, which will have to be maintained practically indefinitely, A Nuclear Commission headed by Jürgen Trittin of the Green Party, who had been involved in the original nuclear phase-out agreement of 2002, reached a compromise.

First, the fund was increased to 23.6 billion euros to be paid by the firms concerned. Second, the money is to be paid into a public fund so that it will be available even if a nuclear company goes bankrupt. In return, the German state is now solely responsible for nuclear waste disposal.