Germany has helped to make solar power inexpensive for the world. The challenge now is to integrate large amounts of solar power in the country’s power supply.

Photovoltaics is the term for solar panels that generate electricity. Solar thermal produces heat, such as for hot water supply or space heating. Solar heat can also be used to generate electricity in a technology called concentrated solar power (CSP), though the technology is mainly useful in deserts, not in Germany.

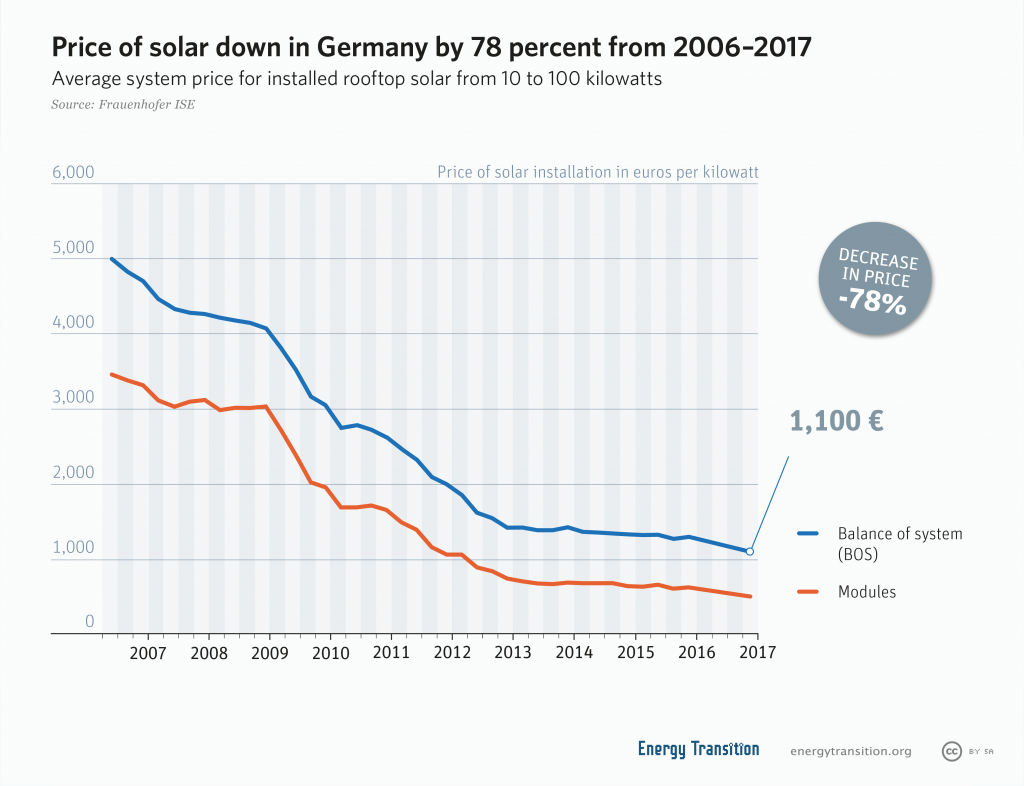

Photovoltaics is what most people think of when they hear the word “solar.” While PV has long been considered the most expensive type of renewable power widely used commercially, prices have plummeted in the past few years (by roughly 75 percent since 2006), and PV is now cheaper than concentrated solar power.

Solar power in Germany

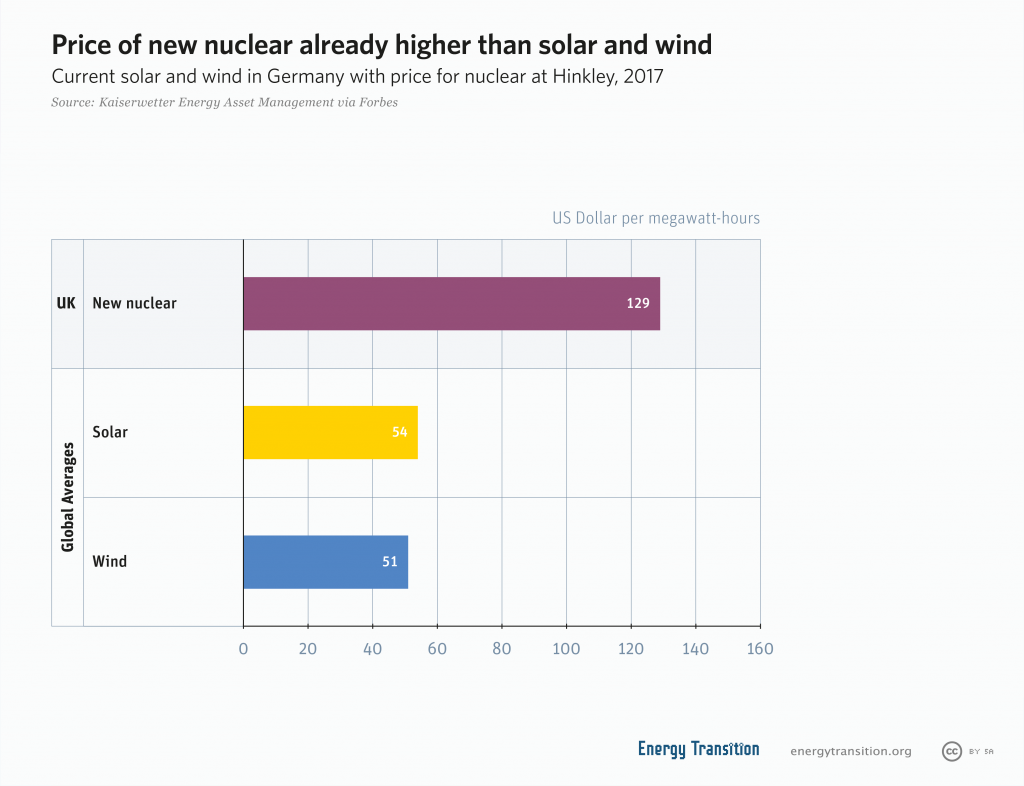

Over the past decade, Germany has been criticized for its commitment to photovoltaics, which was once an expensive technology. But PV now is cheaper than offshore wind, competitive with biomass, and scheduled to become competitive with onshore wind power in the foreseeable future.

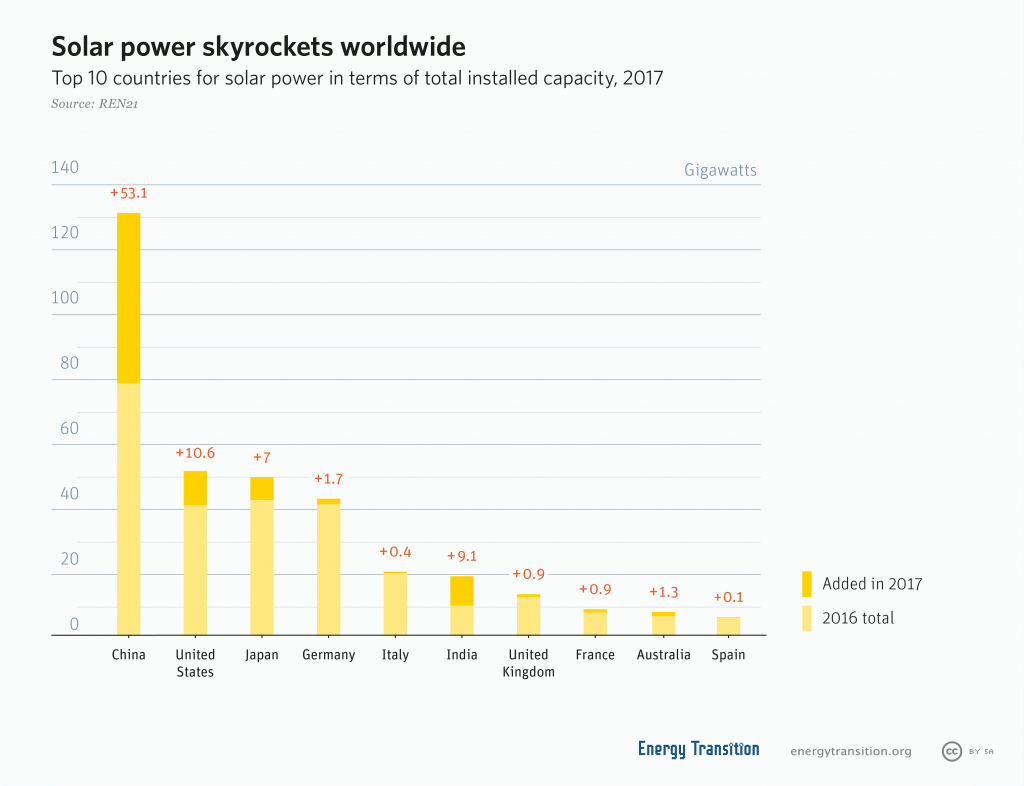

Though not known to be particularly sunny, Germany developed one of the largest solar photovoltaics markets in the world. The price of photovoltaics has plummeted over the past two decades, more than for any other type of renewable energy, and experts believe that it will be competitive with coal power sometime in the next decade. Already, solar power can provide up to 50 percent of German power demand for a few hours on sunny days of low power consumption.

In July 2015, the electricity production from PV was, for the first time, higher than from nuclear power. Together with wind, solar power completely replaced all conventional energy on May 1st, 2018 making up 37% of the energy mix. But the German example also shows that power markets will need to be redesigned for solar to go further because solar drives down wholesale power rates, making backup power plants increasingly unprofitable.

In absolute terms, Germany has more PV installed than any other country except China, Japan and the US. But perhaps the most important comparison is installed PV in relation to peak summer demand. After all, the most solar power is generated on summer afternoons.

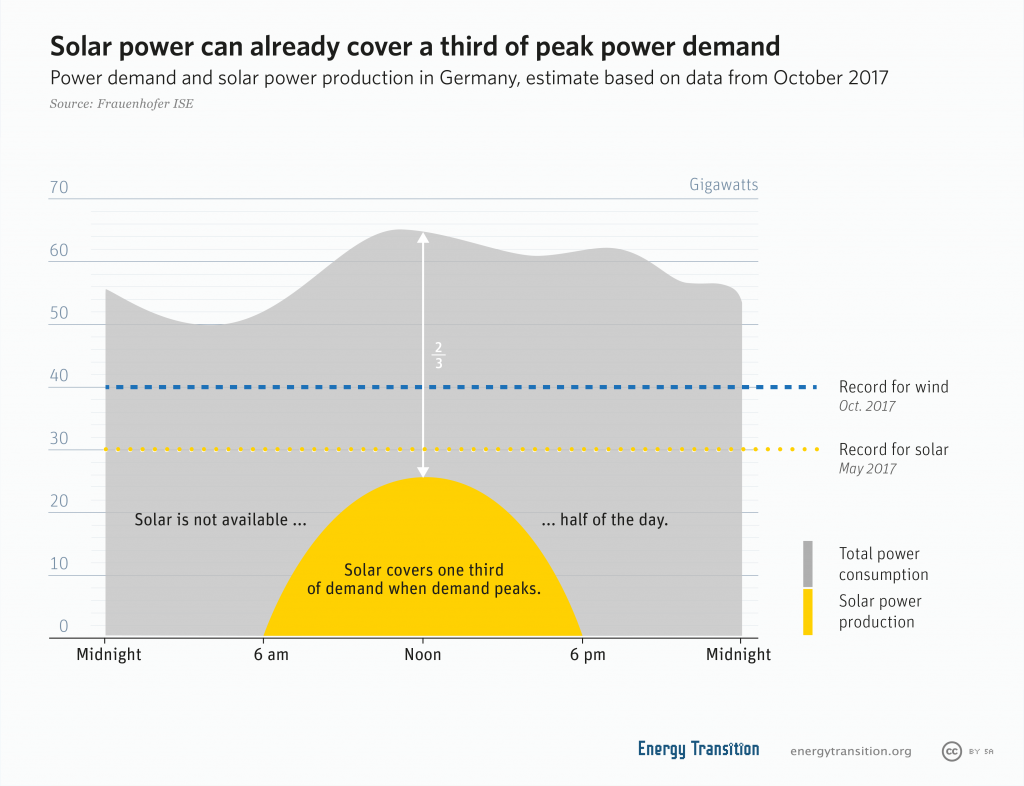

In Germany, power demand is lower in the summer than in the winter because Germans can largely do without air conditioning in the summer, whereas a lot of electricity is needed in the winter for heat, lighting, etc. On April 30, 2017, German solar production reached an all-time peak at 27.6 gigawatts, peaking at a third of total power demand, though solar power only made up around a sixth of power demand for the day as a whole.

For years, proponents of photovoltaics have pointed out how production of solar power coincides with peak power demand around lunchtime, so that relatively expensive photovoltaics turns out to be a good way of offsetting even more expensive power generators to meet that peak demand.

Almost everywhere, PV is still an excellent way to meet peak demand – everywhere except Germany, that is, for the country now has so much PV installed that peak demand is no longer an issue. Photovoltaics now offsets a large chunk of the medium load during the summer in Germany and can even offset a bit of baseload production.

One result of all of this solar power is drastically lower profits for the country’s conventional power plant owners, whose plants are now simply no longer able to run at full capacity; in addition, they cannot sell at such high prices because PV obliterates the need for peak power at noontime.

All of this has come about so quickly that politicians are now looking for ways to redesign the German power market to ensure that enough dispatchable generating capacity remains online for those hours in the winter when Germany reaches its absolute peak power demand for the year (around 80 gigawatts). This also happens to be a time when no solar power is available at all. In this respect, Germany offers a unique glimpse into the future of the energy system based on renewable energies.

On the shortest day of 2016, Germany’s installed PV capacity still managed to produce around 7 gigawatts – as much power as five large nuclear reactors – for two hours, thereby helping to offset peak demand for power.