One major aim of the Energiewende is to decarbonize by switching to renewable sources and reduce energy demand by becoming more energy efficient.

Based on a large body of research conducted by scientists from around the world, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which does not conduct its own research but rather reports on the general international scientific consensus, has repeatedly warned that the rampant effects of climate change could be disastrous.

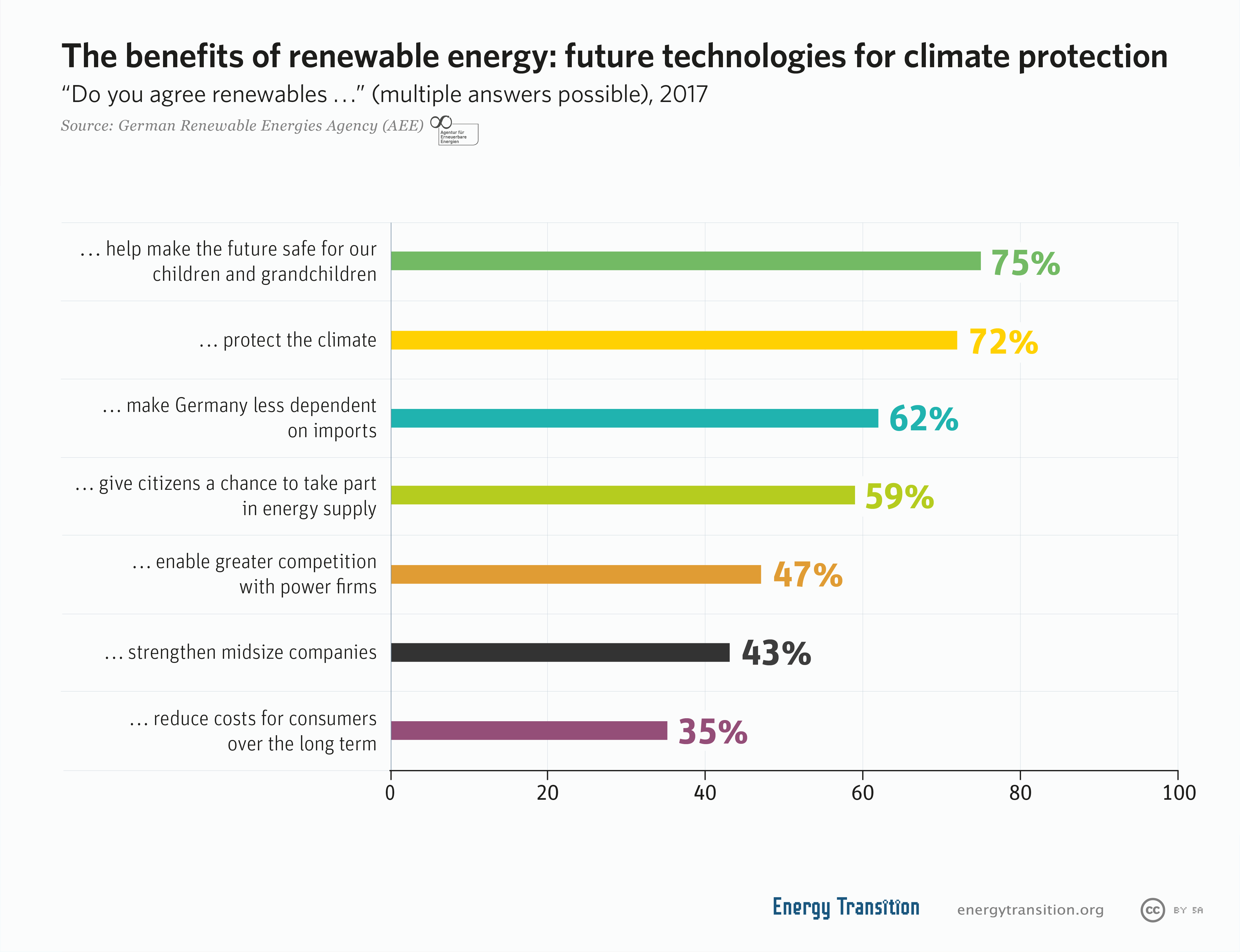

In 2017, a survey found that 84 percent of Germans believe that climate change is a fact. The German business world generally agrees that clean tech is an economic opportunity. After the COP21 conference in Paris, for instance, a group of 34 leading large midsize German firms from a wide range of industries openly declared their support for the agreement and promised to be pioneers in climate protection themselves.

Even skeptical onlookers are coming around: in 2014, only a third of those surveyed by the World Energy Council said that the Energiewende would have long-term economic benefits, compared to 71 percent in 2017.

Yet many German industrial firms continue to fight emissions regulation procedures; for example, the German steel sector voiced its opposition to a floor price on carbon in 2016, and many coal-burning energy companies continue to fight a national coal phase-out.

Policy-makers agree that a carbon floor price of around 25 euros per ton of carbon emissions would already decrease emissions, while 30-35 euros per ton would mean a significant decrease for Germany. These are the prices that France is pushing for within the EU (although for now, apart from Italy, it is alone in this regard).

The current German government does not seem likely to go for a carbon floor price approach, neither within its borders nor in the EU. Some argue that at the end of the day, floor prices are not most efficient way to reduce emissions, as they still cost more per ton of carbon reduced than other measures.

The German public, at least, feels a responsibility to act. They understand that they are one of the countries that have contributed the most to carbon emissions over the past 150 years, and their current position as a leading industrialized nation brings with it a responsibility towards countries that not only still have a lot of development ahead of them, but will also be more severely impacted by climate change. Germans assume this responsibility mainly in two ways:

- a commitment to international climate funding; and

- the energy transition, called the Energiewende.

The carbon budget

Climate experts say that a certain amount of global warming is unavoidable at this point because the climate reacts with such inertia, and the warming would continue for a few decades even if carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere were to stabilize at the current levels – which are drastically higher than anything in recent history. Around the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, the atmosphere had 280 parts per million (ppm) of carbon dioxide, but we now exceed 400 ppm.

In order to keep the planet from heating up more than two degrees Celsius, which would prevent the most disastrous changes, we need to keep that figure from rising above 450 ppm. Many scientists believe that returning to 350 ppm is a good long-term goal, but that would require a net subtraction of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere – at present, we continue to add CO2 to it.

Relative to 1990, Germany reduced its carbon emissions by 27.7 percent at the end of 2017, thereby surpassing its target for the Kyoto Protocol of 21 percent for the end of 2012 in the process. Germany aims to go further, with an 80 to 95 percent reduction by 2050. For 2020, Germany has a voluntary target of a 40 percent reduction that is unfortunately unlikely to be met due to still high levels of coal generation and a lack of progress in electrifying the heat and mobility sectors. If business continues as usual, the reduction will probably be more like 32% relative to 1990.

But technically, Germany could meet its emissions goals by shutting down its dirtiest coal plants. In 2017 about a third of Germany’s emissions came from the energy sector, which has enough energy to easily shut down the worst offenders and still maintain a reliable supply (although it would have to import more electricity; as of now, Germany is a net exporter). Unfortunately there is a lack of political ambition from the German Coal Commission, which prioritizes stability in coal regions, rather than accelerating a transition non-coal jobs.

While a forty percent drop in emissions may seem ambitious, the industrialized world needs to move even faster in light of the consequences we face. If we are to stay within the “carbon budget” for 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming by the end of this century, no more than 760 gigatons of greenhouse gases can be added to the atmosphere. Each year, around 40 billion tons of such heat-trapping gases are emitted; at that rate, we would use up this budget in only 18 years, meaning we would ideally need zero emissions globally starting in 2035.

Furthermore, if we admit that developing countries have a right to increase their emissions slightly as they develop, then the burden of lowering emissions falls even more upon already industrialized countries. In other words, Germany needs to reduce its emissions by 95 percent, not 80 percent by the middle of this century.

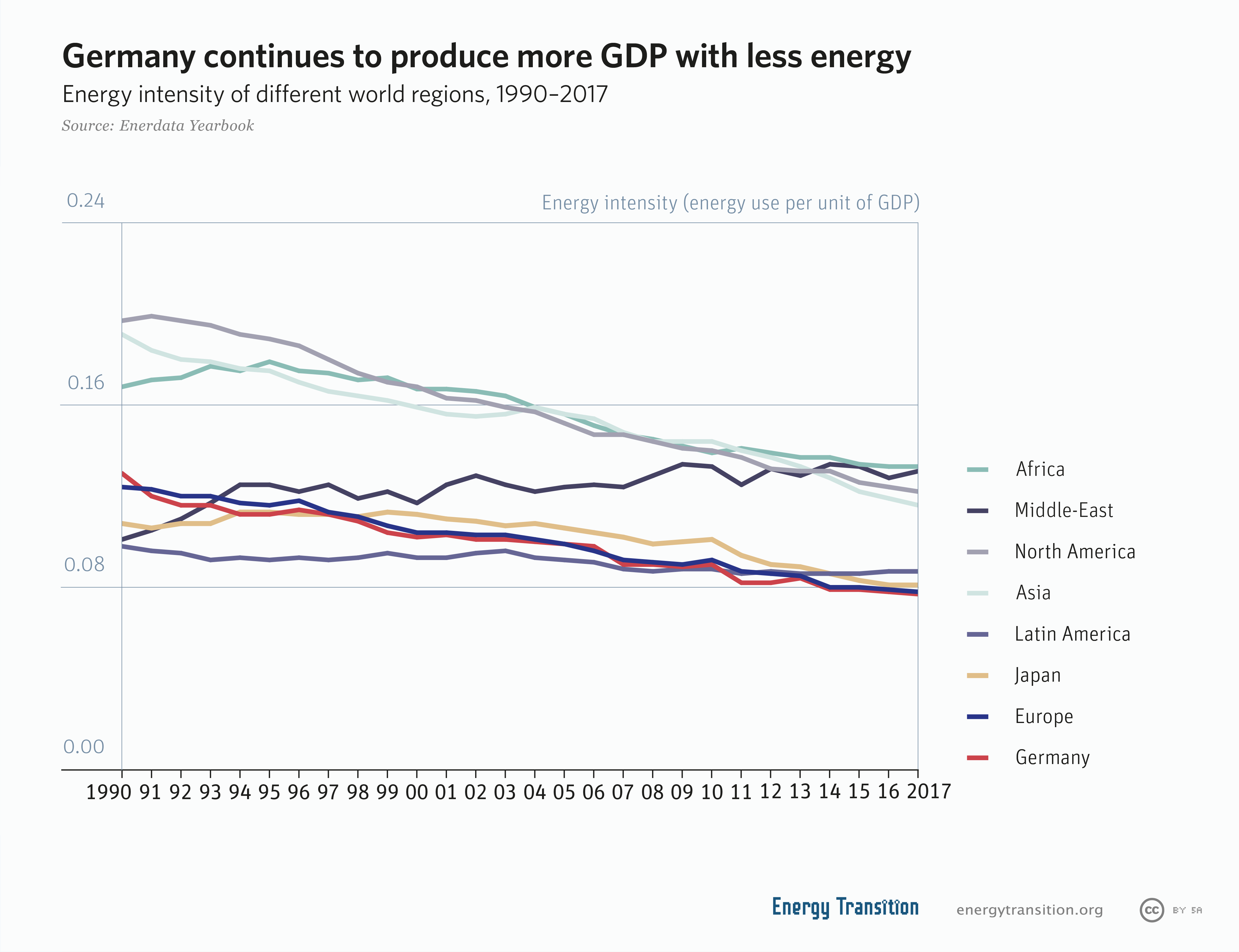

Note that a reduction in emissions will not necessarily lead to less economic growth; from 1990 to 2016, EU member states reduced their carbon emissions by 22 percent even though GDP rose 53 percent. In 2017, Germany’s economy grew by 2.2 percent, while greenhouse gas emissions dropped by around 0.5 percent.

Renewables and efficiency are the solution

Germany produces several studies a year on what a 85-90 percent carbon reduction might look like by 2050 – without reducing the standards of living. The short answer is that we can first become considerably more efficient in order to reduce energy demand, including demand for heat; parallel to that, we switch our energy supply over to renewables. The transportation sector will be a major challenge, where a wide range of solutions will be needed, and Germany is far from reaching its goals of electrifying its transportation sector.

Many efficient technologies are already available, such as LED lights instead of conventional light bulbs. When it comes to air conditioning and heating, passive houses can provide pleasant levels of comfort at very low levels of energy consumption. Electric vehicles are finally becoming more popular as well. Aviation and long-distance shipping remain fields where renewable solutions are more complex, however progress is being made: there are solar shipping vessels in the works.

Renewables are becoming competitive

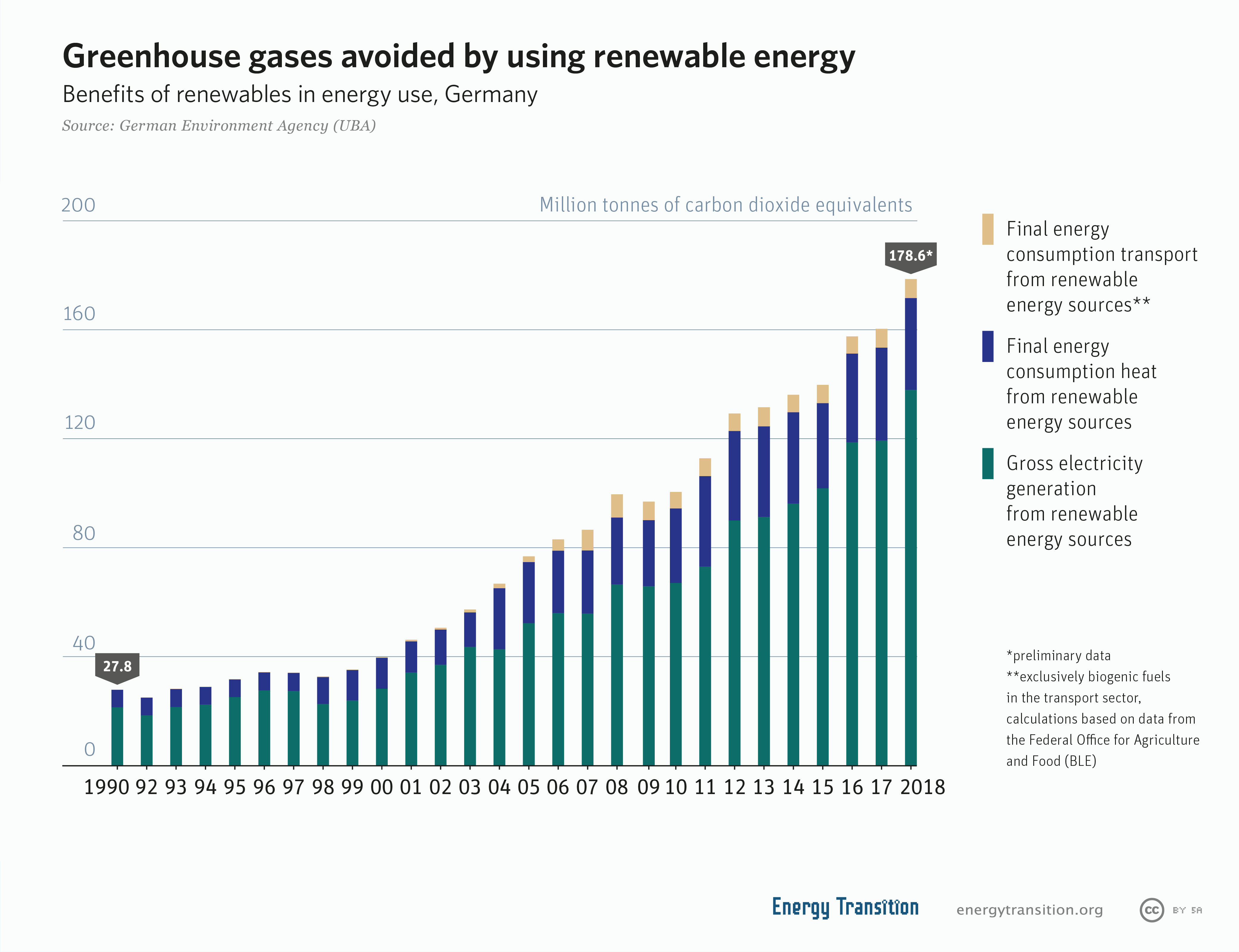

Renewables can increasingly cover a larger share of the energy we still have to consume. In Germany, renewables offset an estimated 178 million tons of CO2-equivalent emissions in 2017, around 104 million tons of which was in the power sector alone. Biomass is also generally carbon-neutral, meaning that the amount of carbon emitted is roughly equal to the amount that the plants bound during growth.

In addition to climate change, the energy transition to modern renewables will improve health conditions by reducing air pollution from coal plants and traditional biomass. By switching from cars running on diesel and gasoline to cycling, public transportation, and electric vehicles, we also make the air cleaner in our cities. These outcomes are called “co-benefits”, and they also include technological innovation, more democratic accountability in the energy sector, and a focus on overall quality of life.