Energy poverty is the lack of adequate warmth, cooling, lighting and the energy to power appliances. More than 50 million households in the EU are impacted by energy poverty.

Energy poverty is related to income poverty, but it is not the same. In spite of being income-poor, a household may not suffer from energy poverty because a district-heating system supplies it with affordable heating. Households that are slightly better-off in terms of income may have to pay more and still end up with inadequate heating because of high energy prices and poorly insulated housing.

The most efficient way to combat energy poverty is to implement energy efficiency measures, including renovating low-income households. This both improves people’s quality of life, and lowers overall energy use (and therefore emissions).

Energy poverty in Germany

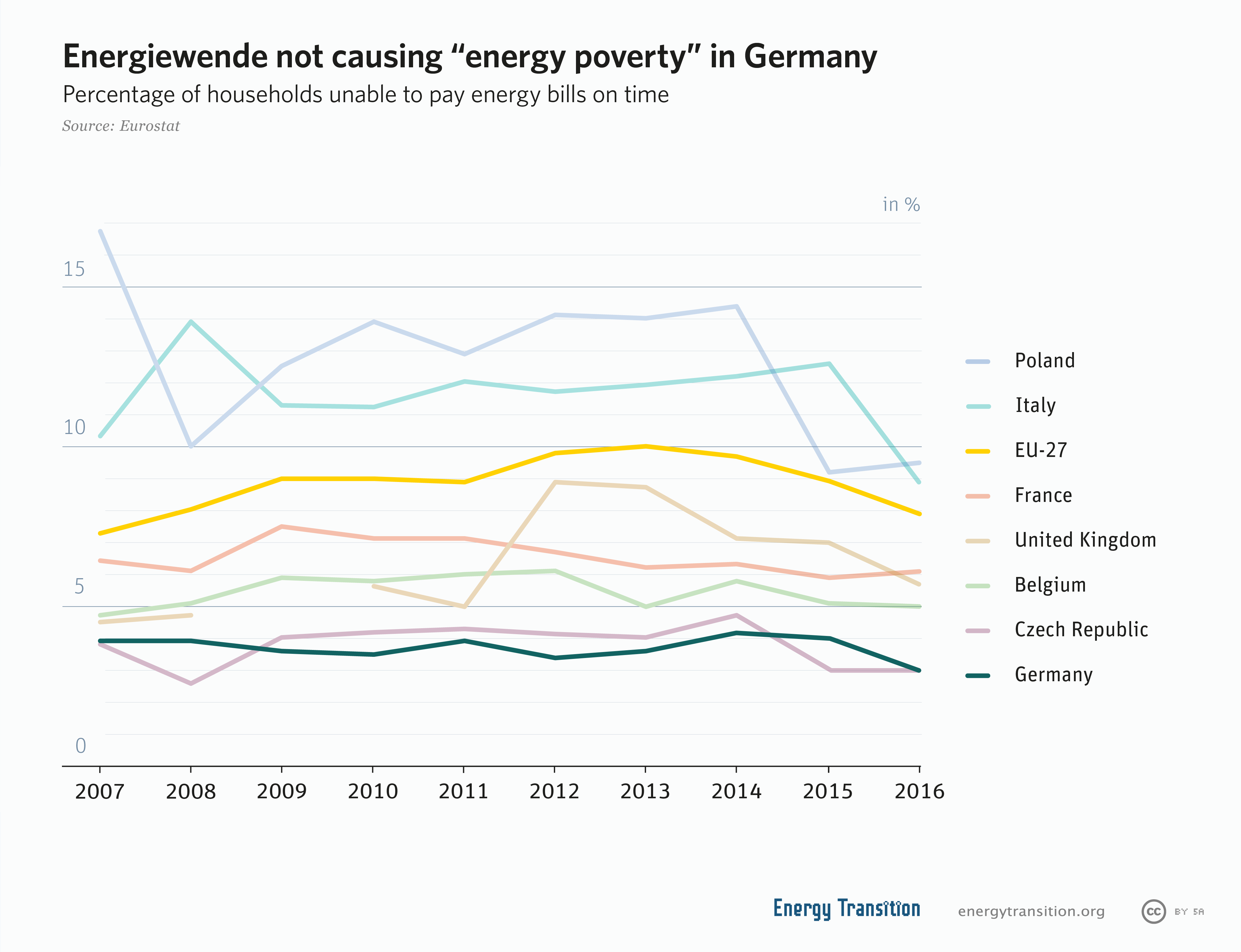

Germany has relatively low rates of energy poverty compared to other EU countries because the inability to pay bills is not just due to energy prices, but also due to country poverty levels and social support.

Rising energy prices impact low-income households the most; after all, on average they spend a higher portion of their income on energy needs and are the least likely to be able to afford investments in energy efficiency such as energy renovations, efficient appliances, and fuel-efficient vehicles.

Energy poverty in the EU

An estimated 50 to 125 million people – between 10 and 25 percent of the EU’s population – are at risk of “energy poverty”. That has serious consequences for both the individuals and families concerned and for society as a whole: low quality of life, health problems, and economic and environmental impacts such as illegal wood cutting and air pollution from burning unsuitable material.

There is no common definition of energy poverty at EU level. Indeed, less than one-third of the EU’s member states officially recognize energy poverty, and only four – Cyprus, France, Ireland and the United Kingdom – have a legislated definition.

The topic was finally put on the political agenda in 2016, in a speech given by Maroš Šefčovič, the Vice-President of the European Commission in charge of the Energy Union, the project to coordinate the transformation of Europe’s energy supply.

Two related initiatives – the EU Fuel Poverty Network and the European Energy Poverty Observatory – will play a key role in developing a common definition. In addition to formulating indicators to measure energy poverty, these two organizations are disseminating information as well as facilitating stakeholder and public engagement on this issue.

Vulnerable countries

Energy poverty is particularly prominent in eastern and southern Europe.

In Bulgaria and Lithuania, an estimated 30 to 46 percent of households struggle to keep their homes warm. In countries such as Portugal, Greece and Cyprus, 20 to 30 percent of households suffer from energy poverty. In Bulgaria, the lack of access to affordable energy and unfair practices by energy monopolies have led to big demonstrations and even the resignation of the government in 2013.

Tackling energy poverty

How to tackle energy poverty? Most initiatives treat it as a social problem. Rather than providing short-term benefits, they focus on increasing the income of vulnerable households indirectly and in the longer term – for example by improving the energy efficiency of buildings and by promoting citizen energy and “prosumerism”, the production of energy by consumers, for example using solar panels.

The Picardie Pass Rénovation is a French initiative that retrofits and upgrades buildings, financed through energy performance contracts – schemes where the expected savings are used to pay for the improvements. Les Amis d’Enercoop, an energy cooperative based in Paris, collects donations via the energy bills of its members and uses them to support local initiatives tackling energy poverty. Members of Som Energia, a cooperative in Catalonia, pay an extra charge that covers part of the power bill of more vulnerable consumers.

What should the role of the EU be?

The EU’s Clean Energy strategy calls for the provision of affordable clean energy for all citizens and greater resilience of the European energy market. But uncertainty remains. Is the Clean Energy strategy solely about mitigating climate change, or does it also have a social aspect? How can policies for decarbonizing energy supplies and transforming the grid benefit vulnerable consumers? And how can they be implemented in an economically feasible and socially attractive way?

If the energy transition is to take energy poverty seriously, the measures and objectives put forward in the proposed Clean Energy package must be revised. They must take into account the differences in economic and social situations in the EU’s member countries.

The European Commission indeed aims to strengthen the social aspects of energy efficiency measures, but this may not be enough on its own. Improving energy efficiency should not be the only goal; another equally important aspect is to embrace the changes in the way energy is generated and consumed today.

Community power projects, where citizens own or participate in the production and use of sustainable energy, are an essential element in the energy transition. They enable citizens and communities to harness local resources, increase tax revenues, and create new jobs. They target two of the root causes of energy poverty: low household income and high energy prices. The lower energy-production costs of renewables should cut the power bill. Collectively, citizens can negotiate better prices. And community power projects can be a source of revenues, which local authorities can use to pay for social policies.